Hoping It Might Be So

.jpg)

Did you know that when cows stand up they get on their knees first?

There is an old folk tradition in this country which says that every Christmas night, all over the world the cattle in their barns kneel down in honour of the birth of Jesus, just as, tradition has it, the oxen did in Bethlehem on that first Christmas night over two thousand years ago.

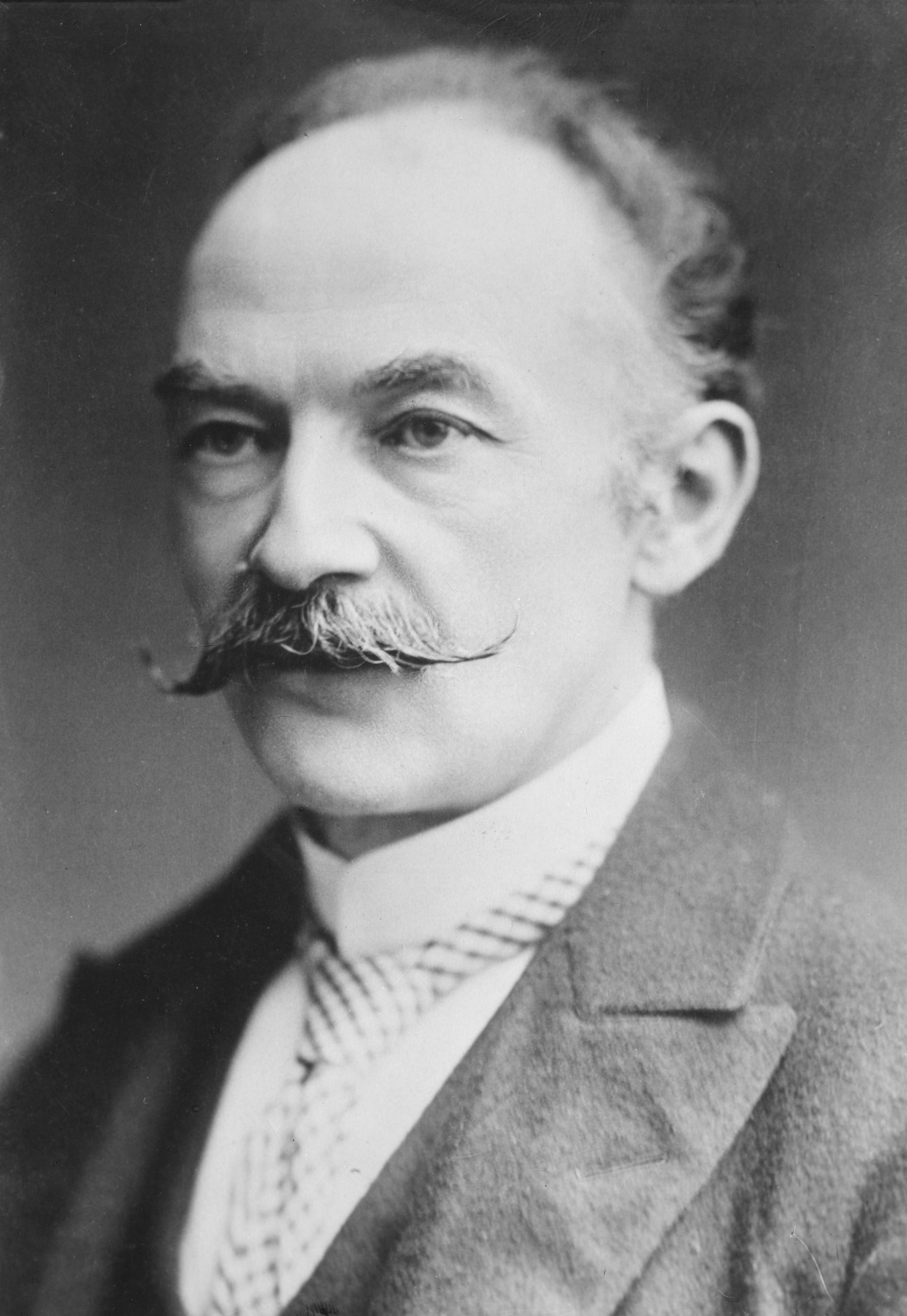

The great English novelist and poet, Thomas Hardy – who wrote novels such as Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Far from the Madding Crowd and The Mayor of Casterbridge – grew up imbued both in these old folk traditions in his native Dorset, and in the Christian heritage of his society. As he grew up, however, he became estranged from his childhood faith, and in his novels comments bitterly on what he saw as the cruelty and hypocrisy of the Victorian Church, such as when the priest in Tess of the D’Urbervilles refuses to bury Tess’s dead baby in sanctified ground because it has not been baptised.

At Christmas 1915, in the midst of the horrors of the First World War, Hardy wrote a poem entitled The Oxen, which alludes to the folk tradition I have explained. Hardy imagines a group of countryfolk, like those who people his novels, sitting round a fire on Christmas night and one of the oldest of them saying with certainty that the cattle will be on their knees now. The educated, worldly, sophisticated Hardy scoffs at such rustic superstition, but nevertheless concludes the poem by saying that, even so, if someone said to him ‘let’s go and see the cows kneeling down’ he would go along, in the hope that it just might be true.

Before I read the poem, a couple of dialect words that Hardy uses which I need to explain: a ‘barton’ is a barn, and a ‘coomb’ is a valley.

The Oxen

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

Christmas is a time of hope – and we will be talking a lot about hope next year, which has been designated a Jubilee year of hope in the Catholic Church. But the hope of Christmas is a different sort of hope from the thin, wishy-washy one where you hope that something will happen even though you know that it probably won’t. Christmas Day will come, two weeks today, and Jesus will be born. The Christian version of hope is of a belief that with God anything is possible, that we – even I - can become perfect and that the world can change for the better, hard though that may be to believe at times. In his play The Winter’s Tale, another of my favourite writers, William Shakespeare, wrote ‘It is required / You do awake your faith.’ Advent is a time for our sleeping faith to wake up.

My prayer as we go our separate ways for the Christmas holidays on Friday is that you will experience a little of the true joy of Christmas, just as those people – and maybe even the animals – did in that barn in Bethlehem, and fell to their knees in response.

God bless you all.